In June of 2020, Palisades Tahoe made the commitment to stop using a derogatory term in its name. After many months of research and working with the community, the resort was renamed Palisades Tahoe in September 2021. For the last year, we have received many questions about this process from our guests. We hear you chatting in the lift line or see you posting on social media. Many still do not understand why changing the name of the resort was such an important step, and we’d like to help everyone better understand everything that went on behind the scenes. We are very proud that we did the right thing, and we are committed to continuing to lead by example in this way.

In this four-part series, we will be doing a deep dive into the history of this valley, the etymology of the word sq**w, the timeline and work that went into the name change, and the future of the resort’s partnership with the Washoe Tribe. With Part One, we would like to introduce you to the Washoe Tribe in their own words. In order to understand why we changed our name, it is crucial to understand the people who were here first. We hope that you will join us to read all four chapters of this story.

All of this information is provided by the Wa She Shu Past and Present booklet created by the Washoe Tribe of California and Nevada, which can be downloaded in full here. This is an abridged version of that information, put together but NOT written by a team at Palisades Tahoe.

A Message from The Washoe Tribe of California & Nevada

Hunga mi’ heshi! (Hello!)

Thank you for your interest in the Washoe Tribe. People that live or travel within Washoe ancestral territory know little to nothing about the past and present of the people and the land. We feel that it is vitally important for all Washoe history as well as the current status of our sovereign tribal nation. This knowledge will help to form a more respectful and complete understanding of Lake Tahoe and the area surrounding it. The Washoe request that you assist in preserving this environment to benefit future generations.

“The health of the land and the health of the people are tied together, and what happens to the land also happens to the people. When the land suffers so too are the people.”

A. Brian Wallace, Former Chairman of the Washoe Tribe

DIT’ EH HU (THE TERRITORY)

The Washoe are the original inhabitants of Da ow aga (Lake Tahoe) and all the lands surrounding it. Tahoe is a mispronunciation of Da ow, meaning “lake.” Washoe ancestral territory consists of a nuclear area with Lake Tahoe at its heart, and a peripheral area that was frequently shared with neighboring tribes. The Paiute and Shoshone live to the east and the Maidu and Miwok to the west. The nucleus of the ancestral territory is bordered on the west by the Sierra Nevada Mountains and the east by the Pine Nut and Virginia ranges, and stretches north to Honey Lake and south to Sonora Pass. The territory takes part of two very distinct ecosystems: the western arid Great Basin region of Nevada, and the forested Sierra Nevada Mountains in California. The variability in climate, geography, and altitude within the territory allowed it to provide a great diversity of foods and other materials essential to life. “As the traditions explain, the Washoe did not travel to this area from another place. They were here in the beginning and have always lived here Each cave, stream, lake, or prominent geographical feature is named and has stories associated to it.” (Nevers, 1976, p. 3)

WAGAYAY (THE LANGUAGE)

“The language, culture and the people cannot be separated. The language is the identity of the Washoe People.”

Steven James, Tribal Elder

The Washoe language is unique and unrelated to those spoken by any neighboring tribe. For many years linguists believed Washoe was of a language group with only this single representative in the world. After further investigation, the Washoe language is now seen as a distinct branch of the Hokan language group. Speakers of other Hokan languages are widely dispersed in North America, and extreme diversity between each Hokan language suggests many thousands of years in which they developed without contact with each other. Some people believe that the Hokan speakers are the oldest Californian populations and that as other peoples invaded the west coast they were dispersed leaving only isolated groups.

County to Gardnerville, early 1900s.

WA SHE SHU (THE PEOPLE)

Washoe, or Washo as most of the people prefer, was derived from Wa she shu. After contact with colonists, changed or altered many things in Washoe history including the tribal name. It is estimated that the traditional Washoe population was more or less 3,000, but it is difficult to know. To understand the Washoe you need to understand the environment in which they live. Washoe have always been a part of the land and environment, so every aspect of their lives is influenced by the land. The Washoe believe the land, language, and people are connected and are intrinsically intertwined.

The Family

Family is the core of the Washoe because these are the people that lived and worked together and relied on each other. In the past, families are recorded as rarely fewer than five individuals and only occasionally exceeding twelve in size. A family was often a married couple and their children, but there were no distinct rules about how marriages and families should be formed, and households were regularly made up of the parents, the couple’s siblings and their children, or non-blood related friends. Generally, a family was distinguished by whoever lived together in the galis dungal (winter house) during the winter months.

Winter camps were usually composed of four to ten family groups living a short distance from each other in their separate galis dungal. These family groups often moved together throughout the year. The Washoe practiced sporadic leadership, so at times each group had an informal leader that was usually known for his or her wisdom, generosity, and truthfulness. He or she may possess special powers to dream of when and where there was a large presence of rabbit, antelope, and other game, including the spawning of the fish, and would assume the role of “Rabbit Boss” or “Antelope Boss” to coordinate and advise communal hunts.

Regional Groups

The Washoe were traditionally divided into three groups, the northerners or Wel mel ti, the Pau wa lu who lived in the Carson Valley in the east, and the Hung a lel ti who lived in the south. These three groups each spoke a slightly different yet distinct variant of the Washoe language. These groups came together throughout the year for special events and gatherings. Individual families, groups, or regional groups came together at certain times to participate in hunting drives, war, and special ceremonies. During their yearly gathering at Lake Tahoe, each of the three regional groups camped at their family campsites at the lake; the northerners on the north shore, the easterners on the east shore, and so on. A person might switch from the group that they were born into to a group from another side of the lake.

There were often cross-group marriages, sometimes even between the Paiute and the California tribes. This said, it was very advantageous that a person continued living in the area where she or he grew up because it took an intimate knowledge of the land to be able to find and harvest all the plant food and medicines, and to be a successful hunter year after year. After moving to a new place, even the best gatherer or hunter would know only as much about the place as a younger more inexperienced person. Gathering and hunting successfully were as much about being familiar with the cycles and patterns in the land as they were about having practiced skills.

Contact With The Immigrants

The Washoe had heard about the new intruders before they ever saw one. As the Spanish invaded the California coast to establish missions and convert Indians to Catholicism, the Washoe began to make fewer and fewer trips to the west coast until eventually those trips stopped altogether. Neighboring tribes that escaped into hiding in the high mountains probably warned the Washoe about the invaders. Although White historians have concluded that the Spanish never entered Washoe territory, the Washoe have told stories about them for generations, and some Washoe words, including names for relatively new additions to the Washoe world, like horse, cow, and money, are similar to the Spanish terms.

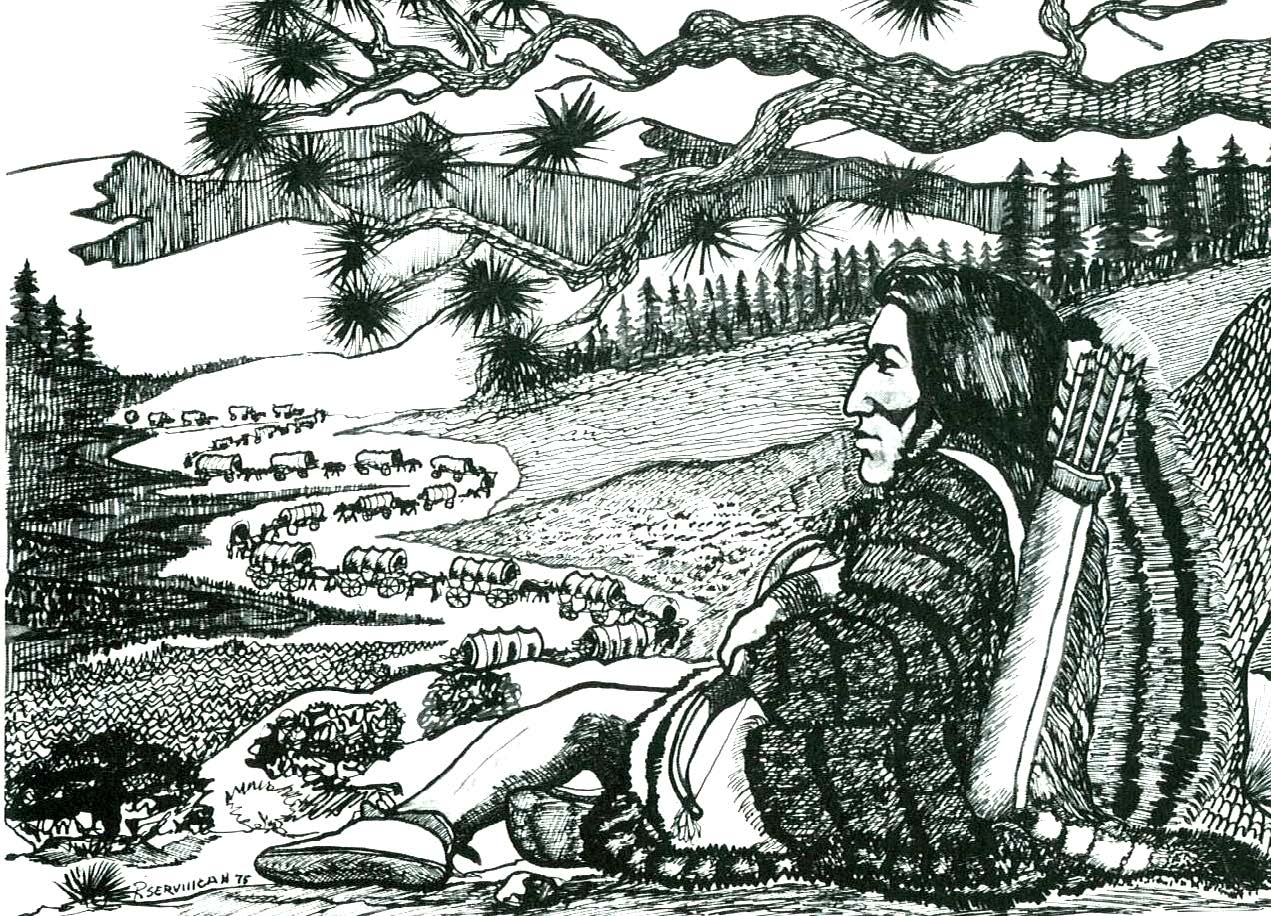

In any case, when the first white fur traders and surveyors began to enter Washoe territory the Indians approached the newcomers with caution. They preferred to observe the intruders from a distance. The first written record of non-Indians in Washoe Land were fur trappers in 1826; they may have met the Washoe, but left no description of the encounter.

The first written description of the Washoe was by John Charles Fremont in 1844, who was leading a government surveying expedition. Fremont described the Washoe as being cautious of being close to them, but in time when he showed no aggression, the Washoe came forward and gave him handfuls of pine nuts, the highest form of hospitality the Washoe could offer a visitor. Fremont described struggling through deep snow and being impressed by the skill with snowshoes. The Washoe willingly shared their knowledge of the land and eventually guided Fremont to a safe passage to California.

As more and more colonizers began infiltrating Washoe land, it was not long before relations grew hostile. The summer of 1844, just a few months after Fremont had passed through, a group of trappers left record of having shot and killed five Indians (either Washoe or Paiute) for having taken traps and perhaps horses. The Indians probably took those things in order to discourage the trappers from entering their land. After the deaths, the trappers searched the area, but not surprisingly found no more Indians. Most westward-migrating settlers had been conditioned by their experiences passing through the country of aggressively defensive tribes of the Great Plains and saw no distinction between different tribes. They expected the Washoe to be violent and dangerous and projected these characteristics upon them.

Destruction of the Land

In1848, gold was “discovered” in California, and although until then most of the Washoe had never seen white people, or had previously avoided them, this soon became impossible. The wagon trains came by the hundreds, and because most of the wagon trails had previously been Indian trails, encounters were numerous. Most of the new people were just passing through, but by 1849 several began to establish seasonal trading posts in Washoe territory. By 1851, year-round trading posts were established, and colonizers became permanent residents on Washoe land. The settlers often chose to live on some of the most fertile gathering areas that the Washoe depended upon.

A few years after gold was found in California, silver was “discovered” in the Great Basin and the “Comstock Bonanza” lured many miners that had passed through back into Washoe territory. The Euro-American perspective viewed land and its resources as objects of frontier opportunity and exploitation. In a short time the colonizers had overused the pine nuts, seeds, game, and fish that the Washoe had lived harmoniously with for thousands of years. By 1851, Indian Agent Jacob Holeman recommended that the government sign a treaty with the Washoe and wrote, “…the Indians having been driven from their lands, and their hunting ground destroyed without compensation therefore – they are in many instances reduced to a state of suffering bordering on starvation.” (Nevers, 1976, p. 49)

All this happened in less than ten years after Fremont had passed through Washoe territory.

Settlers and miners cut down trees, including the sacred Piñon Pine to build buildings, support mine shafts, and even burn as fuel. The Piñon Pine woodlands that had once provided the Washoe, other tribes, and all the animals with more than enough nuts became barren hillsides.

In 1859, Indian agent Frederick Dodge suggested removing the Washoe to two reservations, one at Pyramid Lake, and another at Walker Lake. Because the reservations were intended to be shared by the Washoe and the Paiute, it soon became apparent that this was impossible. Not only did the two tribes speak entirely different languages, but historically they had not always been friendly and trouble would no doubt arise if they were forced to live in close quarters.

Furthermore, the Washoe intended to live on the land where the Maker had created them, and they resisted all attempts to be relocated. Numerous formal requests from Indian agents were made for a separate reservation for the Washoe, but the government ignored them all. By 1865, there were no stretches of unoccupied land large enough within traditional Washoe territory to form one reservation, so an agent made a recommendation that two separate 360-acre parcels be set aside for the Washoe. The following year in 1866, a new agent destroyed any hope of this happening when he sent a letter to his authorities that stated,

“There is no suitable place for a reservation in the bounds of their territory, and, in view of their rapidly diminishing numbers and the diseases to which they are subjected, none is required.”

Nevers, 1976. p. 54

Between 1871 and 1877 several more requests for a reservation for the Washoe were made by agents, but again they were not heard. The government made no attempt to secure rights for the Washoe or to stop the destruction of the lands by the colonial culture. Settler’s livestock grazed the land intensely and grasses that had once provided the Washoe with seed were trampled and eaten. Commercial fishing was practiced on everystream and lake in the area and it was not long before the fish were depleted. At the height of the fishing, 70,000 pounds of fish were being sent from Lake Tahoe to Reno, Carson City, and Virginia City. Of course the Washoe were blamed for the depletion of fish and there were several attempts by the colonizers to stop the Washoe from fishing, but the Washoe banded together and restrictions were relaxed. Even so, there were no longer enough fish for the Washoe to subsist on.

Although most of their traditional resources were destroyed in a short time, the Washoe were used to adapting to what their environment provided for them so they began to change under the pressures of colonization. Many settled near white towns and took jobs on ranches and in white homes to make some money. Some hunted and fished and sold their catch to fancy restaurants. They began to wear white people’s clothes. Women wore long dresses, aprons, shawls, and head scarves. Men wore brightly colored shirts and jeans. They continued gathering together to speak their language, play games, and observe sacred ceremonies like those of the pine nut harvest, rabbit drives, and girls’ dance.

Washoe Indian Allotments

Under the requirements of the General Allotment Act of 1887 each individual Washoe finally did begin to receive some land, but it was not until 1893 that allotments were made to the Washoe, and most of the land proved to be virtually worthless. The Washoe claimed the pine nut hills and the area around Lake Tahoe as their ancestral homeland, but because the foreigners had already settled in great numbers around the lake, they were offered the simple choice to accept the pine nut allotments or take nothing at all. Although none of the sites were suitable for homes and few had water rights, the Washoe took them because the sites had the sacred Piñon Pines that still provided the food that sustained the Washoe through winter.

Some Washoe received allotment lands in California, in Alpine County and in the north around the Sierra Valley and Doyle. Although allotments were legally supposed to be 160 acres, some that the Washoe received were only 120 because settlers already claimed to own adjacent springs and other water rights.

The government appointed a special allotting agent that did not even inspect the allotments. Sections of land were given out directly from the office, and it turned out that most of the lots did not have mature trees on them or were completely without trees because they had recently been used for timber. The borders of these allotments were not clearly marked, and even when they were the Washoe continued

to have problems with colonizers that disregarded boundaries. Reports that whites were trying to gain control over Washoe timber and were illegally using the land to graze their animals were made by the Indian Agents to the government several times, but the problem continued even after laws were passed against it.

Basketry as Art

During the late 19th century the Washoe became famous for their skills in basketry. Colonizers saw the intricate tightly woven baskets that had previously been used for cooking or holding water, and began valuing them as a high form of art. Several Washoe women emerged as outstanding basket makers, including Maggie Mayo James, Tillie Snooks, Lena Frank and perhaps the most famous being Dat So La Lee.

Dat So La Lee was born in 1835, and may have met Fremont when he first passed through Washoe land in 1844. In 1871, she met Abram Cohn, a shopkeeper who she approached with a small basket for sale. He and his wife Amy recognized that she was highly skilled and decided to build a house for her and support her so that she could concentrate on making baskets. They worked out a deal that she would make baskets only for them, and for this reason no tribal member possesses one of her baskets today.

In 1919 Cohn took Dat So La Lee on several trips to show her work and make her famous. She did not enjoy these expositions of her techniques because it is Washoe tradition to only teach members of your family. In modern times her baskets have been priced at $1,000,000. During her lifetime they sold for thousands, also a high sum by the standard of her time. Samples of her work can be seen at the Smithsonian, Nevada State Historical Society Museum in Reno, the Nevada State Museum in Carson City, and the Marion Steinbach Indian Basket Museum in Tahoe City, among others.

This concludes the portion of this blog written by the Washoe Tribe. We hope that you will take the time to read through their entire booklet on their people, their culture, and their history, which is available for download here. This is Part One of a Series. Next, please read Part Two: The S-Word.

| Blog Series |

| • Part One: The Washoe Tribe |

| • Part Two: The S-Word |

| • Part Three: The Resort’s New Name |

| • Part Four: The Washoe Tribe & The Resort Today |